Earlier this week, our five-year-old Resident Princess made an observation out of nowhere. “You’re dark brown Mommy.”

I looked up from my reading and nodded. “Right.”

“Darius is dark brown, I’m tan and and Nia’s light brown like Daddy.”

“Uh-huh, but everyone here is black and that’s the important thing Layla.”

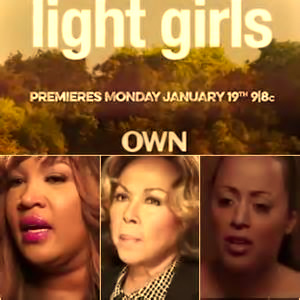

It’s probably odd to other groups that skin hues are quantified in such a manner, but in the black community, the phenomenon known as colorism is as common as drawing breath. Actor, producer and film director Bill Duke first discussed its origins and after-effects in his gripping 2010 documentary Dark Girls and its sequel, Light Girls, will debut at OWN next Monday on Jan. 19.

In its short publicity clip, the upcoming program seems to travel the same precarious path that Dark Girls did—revealing the public shame and private pain of regular and celebrity women who have been marginalized, ostracized or even objectified by other blacks due to the amount of melanin in their skin. “The impact that colorism has,” says spiritual teacher and life coach Ilyanla Vanzant, “leaves scars on the soul.”

I bought the first documentary when it became available as a DVD and we all watched together as a family. Our daughters aren’t technically considered ‘dark’ and none of our kids have been negatively compared or contrasted by shade in this household, but we wanted them to learn early of how the practice started, colorism’s devastating effects and the warped media and societal perceptions that perpetuate them.

As a mother, it frustrates me to know that our African-American children, already saddled with the burden of experiencing racism, will also have to contend with being referred to as “yella,” “light-skinned,” “dark-skinned” or “redbone”—- common colloquisms for skin tones that blacks use among themselves—- and become pigeon-holed further still. It’s beyond pathetic that the amounts of lightness and darkness in pigmentation, over which they have no control, can feed warped and asinine perceptions of intelligence, violent tendencies or even their levels of appeal for employment and the opposite sex.

Although Duke chose, for whatever reason, to focus on colorism’s effect only on black women, black men are also benefactors, as well as perpetuators, of colorism and skin stratification according to Dr. Margaret Hunter. She’s an associate professor of sociology who specializes in race and gender studies at Oakland, CA’s Mills College and served as an expert for the new film.

By phone from her faculty office, Hunter revealed her own biracial background and how impactful she believes the documentary will be in exposing perks and prejudices experienced by blacks with lighter shades of skin. “It’s an ongoing issue and we need to challenge one another, especially black men, to rethink their attitudes toward women and their own concepts of color and beauty,” she says. “More men need to value women beyond that suface level and those narrow perceptions reveal how deeply-rooted and internalized issues of racism and sexism is.”

Since the politics of colorism also hit home personally for Hunter, the professor says that she regularly reinforces to her students and her own children that color should not dictate character.

“Along with my husband, who’s Filipino, I stress that blackness comes in many shades and that identity isn’t connected only to how we look,” she says. “Parents of color really don’t have a choice but to be an altenate voice to mass media, which continues to glorify lightness. We can’t control the likes of a Sony Entertainment or a Warner Brothers, but we can combat colorism by watching Light Girls and launching a frank and open conversation from there.”