“I am alive because of the blood of proud people who never scraped or begged or apologized for what they were. They lived asking only one thing of this world—-to be allowed to be.”

Those words were part of the dialogue spoken by Mrs. Browne, the mother of a naive and stubbornly independent daughter, during the 1989 mini-series, The Women of Brewster Place. From any other woman, the lines could have just been a matter of fact, but when they shot from the mouth of the actress Cicely Tyson, who died last month at the age of 96, they rumbled with a resonance that lifted the speech to stratospheric heights. Watching her recite them made the viewer both pay attention and absorb their weight, because like every other role she played, the late Ms. Tyson embodied the character’s very bone structure and spoke the sentiment from her soul, like a life-honed mission statement.

It’s going to be hard to navigate a world bereft of such a gifted and galvanizing performer. For today’s generation, she was Viola Davis’ mother Ophelia in the ABC series, How To Get Away With Murder, and spirited sages that spoke love and wisdom to friends and family members in three Tyler Perry films, 2005’s Diary of a Mad Black Woman, 2006’s Madea’s Family Reunion and Why Did I Get Married Too. But for me, the shy choir girl-turned stage and screen icon was Rebecca Morgan in Sounder, Binta in Roots, the resolute Jane Pittman and schoolteacher-turned-student advocate Vivian Perry (opposite the late Richard Pryor) in 1981’s Bustin’ Loose and as Marva Collins in The Marva Collins Story. Whether it was during a spirited cameo (Sipsey, Fried Green Tomatoes) or a full-fledged mini-series, (Mama Flora in Mama Flora’s Family, 1998), just to name a few, Cicely Tyson infused the roles with dignity, strength and unabashed pride in her blackness, even in a pre-Civil Rights America that tried its hardest to condemn it. The constant reminder by society that I am “different” because of the color of my skin, once I step outside of my door, is not my problem—-it’s theirs,” Tyson says in the 1989 book, I Dream A World. “I have never made it a problem and never will.”

So while I grew up looking to my mother, grandmothers and others in my life on how to carry myself as a young Black woman, I also took silent mental notes from Cicely. She was petite, yet carried herself with the grace and power. Her rich, brown skin, full lips and wooly hair were assets she put on display rather than hide. With her conscious career choices and her self-possessed countenance, Cicely demonstrated to the world, and to generations of black girls to follow, that we were beautiful and worthy of acclaim. While Tyson didn’t consciously set out to become a role model, her insistence of only portraying quality characters, stereotypes be damned, paved the way for a newer generation of actresses play boldly and broadly on a world’s stage.

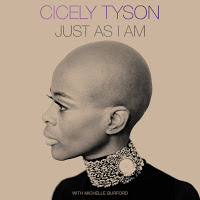

Today, as I watch Cicely Tyson’s films and plays, while plunging into intimate wisdom of her newly-released memoir, Just As I Am, I remain inspired by her accomplishments and who she was: a sister, daughter and mother who deliberately used her gifts and wide-ranging platform to advocate for us fellow African-Americans, all while the world was watching.

Up until her last moments, she was steely yet stylish, humble and grateful about all she had achieved, from her 2016 Medal of Freedom to being loved and celebrated by peers and fans. In an interview that aired on CBS This Morning, two days before she passed, Tyson revealed that she “had no idea that I would touch anybody. ” “I done my best, that’s all,” when she asked what she wanted to be remembered for. Take your rest, Lady Cicely….your best is what we now remember and cherish. Forever.

6ck2le

Such an icon, she will be loved forever.