On a day-to-day basis, more often than not, I consider myself to be a confident woman. I’m grateful for what I have, work with what I’ve got and usually look forward to where the adventure of life will take me next as a wife, mother and journalist.

But Saturday’s Fourth of July will be tainted by the news stories that highlights this country’s constant tensions with race, underscored with images of burnt churches, bullet-ridden cars and broken, bloodied bodies. It’s enough to sap the strength of even the most seasoned of journalists, including me. The New York Times recently explored the anger, anxiety and despair that plague the lives of African-Americans in an article titled “Racism’s Psycological Toll.”

But Saturday’s Fourth of July will be tainted by the news stories that highlights this country’s constant tensions with race, underscored with images of burnt churches, bullet-ridden cars and broken, bloodied bodies. It’s enough to sap the strength of even the most seasoned of journalists, including me. The New York Times recently explored the anger, anxiety and despair that plague the lives of African-Americans in an article titled “Racism’s Psycological Toll.”

Shortly after the racially-motivated mass murders in Charleston, SC, writer Jenna Wortham spoke with Monnica Williams, a professor, psychologist and director of the University of Louisville Center for Mental Health Disparities about the individual and collective damages of racism. According to Williams, the stressors and traumas nearly universally-experienced by those victims of racism should be seen as comparable to the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder “because the African-American community has such a long history of pervasive discrimination.”

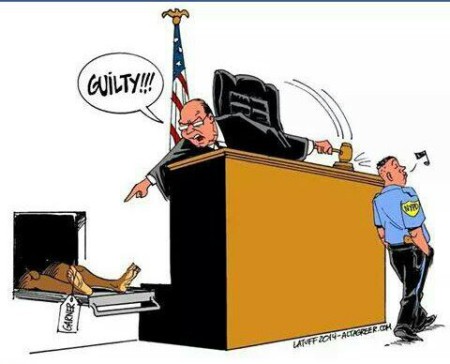

I can see Williams’ point. For people of color, no matter what era, income bracket or gender they’re born into, the insidious nature of being challenged perpetually to prove one’s worthiness of basic humanity is a neverending battle that few whites will fully understand and most blacks never seem to win.

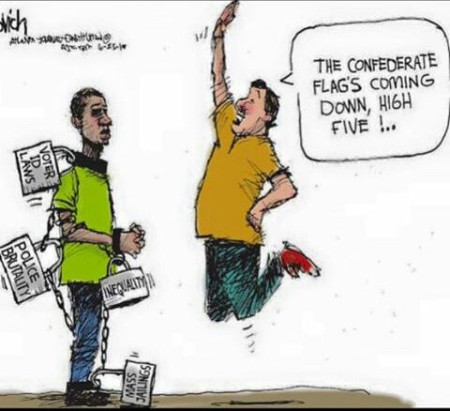

The frustration comes from the inconsistent barameters of acceptability that blacks are graded against, as well as the steady stream of dissenters who argue, despite documented proof and evidence to the contrary, that such scales even exist. It’s no different from a man telling a woman that the pain of childbirth is exaggerated or assault victims being chided that their actions precipitated the attack. For blacks, racism doesn’t always occur as overtly as a flaming cross on the front lawn, crude caricatures in anonymous letters or the nasty n-word hurled into your face. Most of the time, it’s death by a thousand cuts. As stated so succinctly by the Pulitzer-Prize-winning author, Toni Morrison, “…..The very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. ……None of that [explaining] is necessary. There will always be one more thing.”

Sometimes, it boils to a matter of perspective. Those who lived in the Jim Crow pre-Civil Rights era, like my mother and father, believe that racism’s presence, or at least its most egregious effects, have greatly abated. They have watched the literal ‘whites only’ barriers tore down, school desegregation and a man with a Kenyan father and American mother become President of the United States. I am grateful to live in this era for the time in history we now live in and for what has been accomplished in the name of Civil Rights.

But what I still truly yearn for—-the erasure of the generational and systemic protections that empower racism—-has yet to arrive. And until that takes place, our generation, our children’s and those yet to be born will continue to buckle under the weight of, and even lose their lives to, the illusive and artificial standard created by “one more thing.”