“Why is that there is a gun shop on almost every corner in this community? …for the same reason that there’s a liquor store on almost every corner in the black community. Why? They want us to kill ourselves. You go out to Beverly Hills, you don’t see that [expletive]. But they want us to kill ourselves…. Who is it that dyin’ out here on these streets every night? Y’all. Young brothers like yourselves. … You doin’ exactly what they want you to do. You have to think young brother, about your future.”

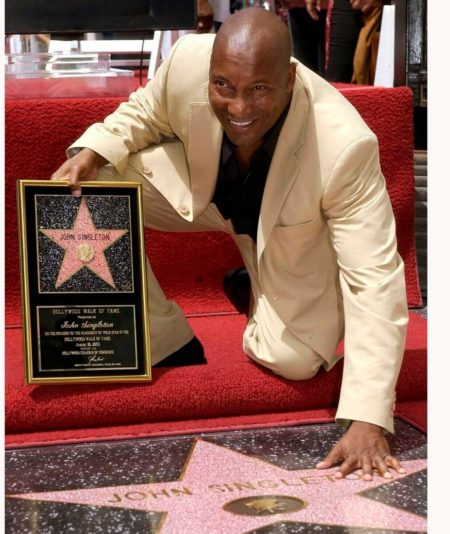

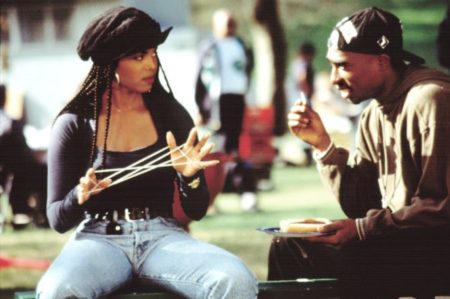

I was just a teen when I watched the film, Boyz N Da Hood, and that monologue by the Lawrence Fishburne’s character, Furious Styles, resonated in my heart and mind long after the credits rolled. Expectations were already high then for the coming-of-age film, but what made it an unforgettable classic was the searing visuals, relatable storyline and the lessons presented with eloquence and insight by a then-24-year old USC film graduate, John Singleton. When he passed away unexpectedly this week at the age of 51, the Academy-Award-nominated producer, director and screenwriter left behind an incredible body of work that launched countless careers and inspired a new generation of filmmakers in the process.

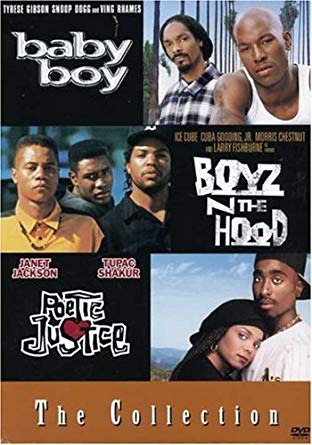

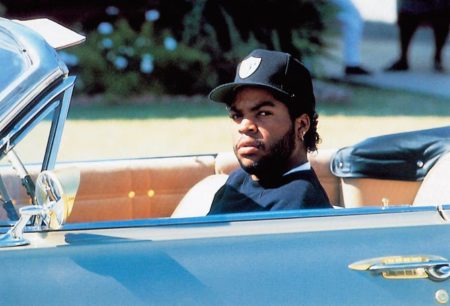

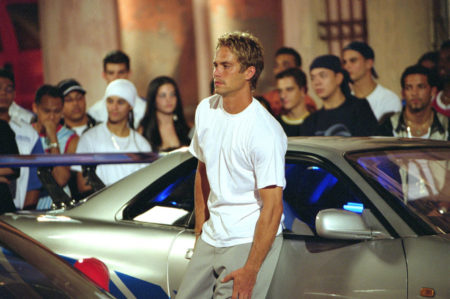

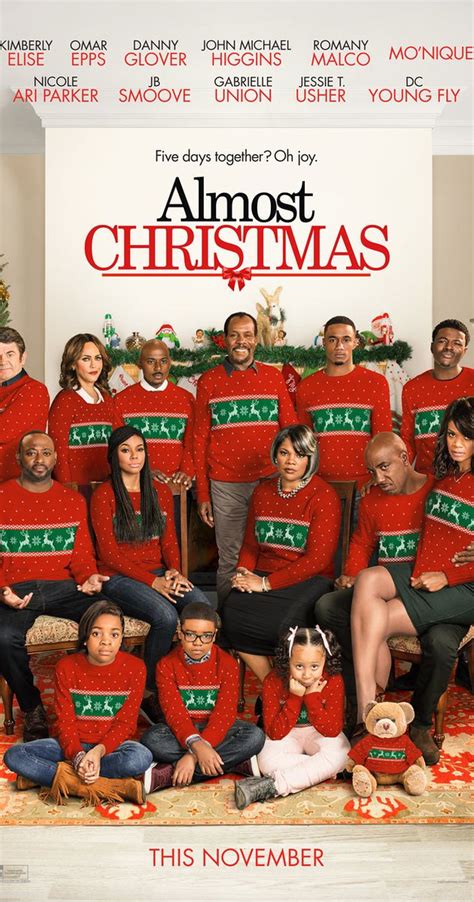

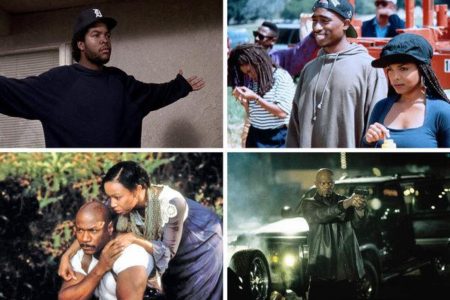

From that movie forward, John Singleton became one of my very favorite filmmakers, partially because of Boyz’ message and its wel-encapsulated exploration of experience of urban contemporary ‘street life,’ a world so unlike my own. The horrors of gang violence, police brutality, dreams deferred and crushed under the weight of sunken expectations and families who strove every day to rise above…..only an LA native could have tied those elements together so deftly. Yes, there were other important films too: Higher Learning, Poetic Justice, Rosewood, Hustle & Flow and 2 Fast, 2 Furious among them, and what united each one all was his keen eye for detail, his unique African-American undercurrent and dialogue rich with history, humor and heartbreak. Young people today have the privilege to grow up impacted by the voices of new movie makers like Barry Jenkins (If Beale Street Could Talk, Moonlight), Will Packer (Girls Trip, Night School), George Tillman (Soul Food, Notorious) and Malcolm Lee (Girls Trip, The Best Man) and Gina Prince-Bythewood (Beyond the Lights, Love & Basketball), but their artistic evolutions would have had much rockier roads to navigate had John Singleton not been there to pave it.

From that movie forward, John Singleton became one of my very favorite filmmakers, partially because of Boyz’ message and its wel-encapsulated exploration of experience of urban contemporary ‘street life,’ a world so unlike my own. The horrors of gang violence, police brutality, dreams deferred and crushed under the weight of sunken expectations and families who strove every day to rise above…..only an LA native could have tied those elements together so deftly. Yes, there were other important films too: Higher Learning, Poetic Justice, Rosewood, Hustle & Flow and 2 Fast, 2 Furious among them, and what united each one all was his keen eye for detail, his unique African-American undercurrent and dialogue rich with history, humor and heartbreak. Young people today have the privilege to grow up impacted by the voices of new movie makers like Barry Jenkins (If Beale Street Could Talk, Moonlight), Will Packer (Girls Trip, Night School), George Tillman (Soul Food, Notorious) and Malcolm Lee (Girls Trip, The Best Man) and Gina Prince-Bythewood (Beyond the Lights, Love & Basketball), but their artistic evolutions would have had much rockier roads to navigate had John Singleton not been there to pave it.

Part of what’s so painful about Singleton’s passing is the loss of not only a partner, a father and mentor, but an unbridled critic of the commonly stunted and self-serving templates that Hollywood often perpetuates for African-Americans in front of, and behind the camera: “They ain’t letting the black people tell the stories,” Singleton told an audience of students at Loyola University in 2014.” They want black people to be who they want them to be, as opposed to what they are. They’re not moving the bar forward creatively. …When you try to make it homogenized, when you try to make it appeal to everybody, then you don’t have anything that’s special.”

John Singleton, along with his peers, used films to not only tell stories, but to broaden the scope and the range of how African-Americans are portrayed in films and therefore, within the media and popular culture itself. He cast hungry young actors like Taraji P. Henson, Morris Chestnut, and future Academy-Award winners, Regina King and Cuba Gooding Jr., respectively, and unfamiliar roles that stretched and emboldened them. Singleton also amplified the already-burgeoning careers of Ice Cube, Tyrese Gibson and Terrence Howard and translated their natural charisma into characters that diverse audiences could learn from and relate to.

To paraphrase a famous phase from Boyz, any fool with a camera can make a movie, but it takes a true visionary to make a masterpiece. And before he died, on big screens and small screens, John Singleton achieved just that.