“A child cannot be taught by anyone that despises him.” – James Baldwin

As a member of Generation X, I moved from Ohio to Texas with my family in the late 1970s. To hear my parents tell it, the decision was made to leave our hometown of Cleveland, a city facing a steady decline of manufacturing jobs, to the still-burgeoning industries found in Dallas. My father’s training in refrigeration and air conditioning was well-suited for the South, and months after arriving in the Lone Star State, we settled into apartments, then rental homes, always within or bordering the suburbs.

My siblings were practically babies and I was in grade school, so we were all too young to realize what my parents’ objectives were in moving us to places like North Dallas, Richardson, Garland and Mesquite: safer living areas for all of us and higher quality schools –even if we were the only Black students in each classroom.

Perhaps my mother and father understood, with their personal experiences with the daily indignities of Jim Crow and the dehumanizing undercurrents of segregation, that the landmark decisions to desegregate the schools established in 1954 (Brown vs. Board of Education) and the 1965 law that granted civil rights to minorities (Voting Rights Act) would take time to be fully implemented.

The policies needed to be expanded and rewritten, funding needed to be redistributed and watch guards needed to be installed, as well as enforcement channels and procedures that guaranteed the still hotly debated laws would be obeyed.

Schools blighted by environmental neglect, struggling staff and outdated materials due to the racial makeup of their citizens hoped to elevate in time, but the changes could take years to correct, which is why the Trump Administration’s insistence on now removing desegregation orders is a troubling one.

The rollback started in April, due to pressure from Louisiana’s Republican Gov. Jeff Landry, along with the state’s attorney general. Despite proven and long-lingering racial disparities in admissions, student discipline and the hiring of staff, enforcement of the orders (mostly created in the 1960s and 1970s) is considered burdensome and unnecessary.

What the administration and the Louisiana governor failed to understand, or are overtly ignoring, are the remaining discrepancies still affecting non-whites in Louisiana as well as across the nation.

Children in predominantly Black areas are often forced to attend crumbling schools near toxic sites, are academically stunted by dated and dilapidated learning materials and also endure disproportionately high disciplinary measures in comparison to their white peers. Even with desegregation orders in place, inequities remain, and removing mechanisms that prevent direct access to the justice department or relief from courts leaves vulnerable families with tedious and expensive lawsuits as their only recourse.

Another consideration lost in the pursuit of the desegregation protection removals is why diversity matters in the first place: fostering awareness of, and embracing the reality of, other groups and cultures. If my family and I had remained in Cleveland and I had only grown up with people who resembled me, it would have definitely been more comfortable, yet less challenging.

Coming of age in close proximity to peers of different backgrounds enriched and educated me in ways that I still benefit from today. Ignoring the prevalence of systemic racism, past and present, won’t make dealing with diversity any less essential or difficult, and scrapping legal precedents will only inhibit the progress we’ve slowly, yet painstakingly, made.

Along with the flurry of President Trump’s executive orders attempting to remove the implementation, and effects of, diversity, equity and inclusion, the efforts to dismantle the safeguards of desegregation appear to overlook the obvious: America will never truly be “great” if its leadership and learning institutions fail to acknowledge the worth and contributions of all. Especially when they happen not to be white and male. And 60 years, a little over half a century, is still not long enough to eradicate the generational poverty and systemic pitfalls that once-lawful prejudicial policies created.

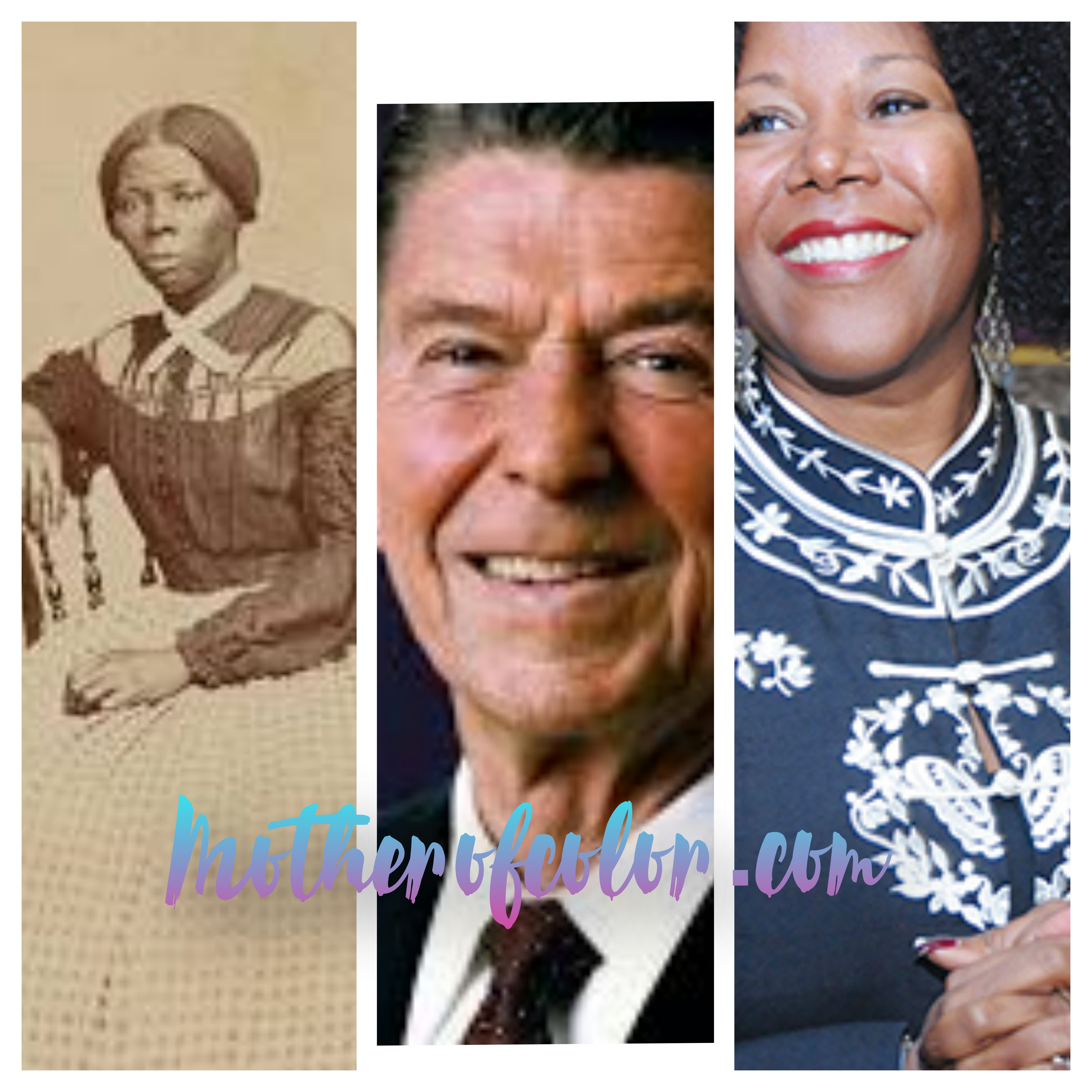

Ultimately, those in a hurry to “move on” fail to recognize how close ‘the past’ is to the present and how relatively short 60 years is in the arc of our nation’s 299-year-old history. Women and so-called minorities have been equal citizens under the law for little over half a century. Harriet Tubman, one of the world’s most famous formerly enslaved freedom fighters, was still alive when Ronald Reagan was born in 1911. Ruby Bridges, at the tender age of 6, became the first African American student to desegregate LA’s William Frantz Elementary School in 1960. She turned 70 last year. So when critics of corrective measures aimed at leveling the playing field say segregation and Jim Crow were ‘a long time ago,’ ‘long’ is relative.

I am proud to have lived through, and been on the receiving end of seismic cultural shifts: the growth and expansion of women’s rights, space exploration, and evolving in real time from analog to digital technology. But what I have yet to witness —children like yours and mine fully realizing their educational potentials in a system that recognizes their differences while celebrating them.

Lorrie Irby-Jackson is a freelance columnist and entertainment writer in Dallas.